|

ARTICLES ON THE ARTIST patina of life

Paintings of rich, rural scenes pay tribute to the grit and strength of Douglas Wiltraut’s subjects, their environments and their homes in a manner akin to Regionalism or the American scene painting movements of earlier eras. Here, romantic conceptions of farm and yard, child and worker are cast in dramatic sunlight with a quiet and reserved beauty. We see signs that Thomas Hart Benton has been here—and Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth, too. In the dappled sunlight we may think of Vermeer and perhaps of Velázquez, influences Wiltraut is quick to point out. Nevertheless, the artist’s greatest inspirations, we see, lie far closer to house and home, and draw heavily on his own memories. “Many of these paintings have ties to my early childhood, particularly to the function of the backyard,” he explains. “The backyard was the Mecca, the hub of all family social activities, and I’ve attempted to portray the backyard as a symbol of family life.” While the tenets of Regionalism, in part, expressed anxiety over the growth of cities in decades past, Wiltraut’s concerns reflect more personal, contemporary issues. “There used to be an affection for the backyard and for all the activities that took place there—celebrating birthday parties, hanging wash, playing with the dog, cutting the grass and planting the garden,” the artist says. “All these things, coupled with the images of the backyard hammock, the sandbox, the swing set, the slide, the wading pool and the tree house, provided so much to fuel the imagination. The sad thing to me is that all of it, except in the most rural areas, has disappeared and been replaced by the sterile suburban yardscape, where you can’t even have a shed or hang the wash.” Inspiration

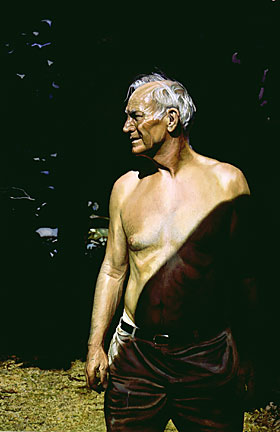

Intrigued by what he refers to as “the patina of life,” the artist often paints pictures that celebrate the proof of time’s effects. “I’m intrigued by the passage of time,” he says, “and the evidence of that passage on people or objects.” In works such as Cracked Rib, The Silent Ax and Mare’s Tail, retired objects assume primacy in their respective compositions, while Gutted and Bone Dry pay homage to vacant structures beyond the point of usefulness. If the figures shown in Reds and Family Man seem similarly timeworn, there is perhaps in these paintings an even deeper feeling of reverence, of respect. Rather than fearing the passage of time, as many of us do, Wiltraut embraces it. “Most people don’t enjoy getting older,” he says, “and they realize as they do get older that time starts to go by more quickly.” By celebrating the wisdom and life experience that comes with age, the artist manages to achieve quiet compositions that resist melancholy. “There’s a beauty to the passage of time and the effects it has on objects and people,” Wiltraut says. “Timeworn textures, a face with a story to tell, the patina of life are all things I like to portray. The passage of time is something we all have to deal with. I almost always paint these objects and people in a strong, raking sunlight with elongated shadows, which results in what I refer to as a ‘special visual moment,’ a moment when the ordinary is elevated to something memorable.” Process In order to paint light at night, Wiltraut uses a sketch or a photograph to record the shape of a cast shadow. He doesn’t see working this way as a hindrance, since the lighting situations he paints are fleeting anyway. Very often, the artist says, he brings objects he’s painting into his studio to create a modified version of his scene indoors to work from, and he uses “instinctive composition” to design his paintings. “When something looks right,” he notes, “it usually is.” For works that contain figures, such as Family Man or Looking at the Moon, Wiltraut begins with the face and skin. “I try to get the facial area fairly close to what I want it to look like before proceeding to the other areas,” he says. “If the face doesn’t turn out right, what’s the point?” Using the English watercolor method, Wiltraut brushes a clear passage of water over the chosen area of skin first before applying a single color to this newly wet spot. After the color dries, a second passage of clear water and a second color are introduced to the same area of the paper. This process continues, layer by layer, until the desired pastel-like skin tone results, he says. Textures and details are added later to these layers with drybrush techniques. Although he sometimes employs a background wash first, Wiltraut usually works around the near-finished figure with a wet-on-dry approach. “When the background value is established to the darkness that I want, I will then go back to the face or figure until I bring the face and background into balance,” the artist says. “Because I love to depict a strong sunlight, my ‘balance’ really is an exaggeration of the values, because it’s that exaggeration that ‘brings the sun out.’ ” Believing that dark passages without detail can flatten rather than enhance a painting with a cast shadow, Wiltraut takes extra care to include intricate detail work in his shadows. “It’s critically important to include details within the shadowed areas to create an illusion of reality,” he says. “When you peer into a dark shadow you can still see things.” Meaning

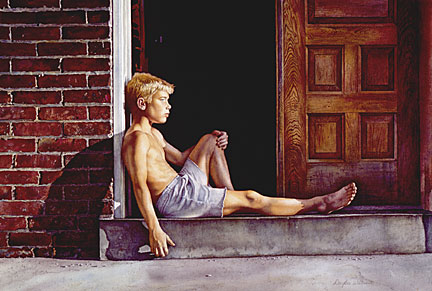

Be it a still life, an architectural landscape or yardscape, or a portrait, Wiltraut’s paintings overwhelmingly express reverence—and wonder—at the space, time and place of their subjects. In Setting Son, we see a young boy—the artist’s son—at rest on the cool, front stoop of a relative’s home after a long day of outdoor play. As the sun casts his face in a healthy glow, we can’t help but notice the shadow gaping behind him from the open front door—and the interior adult world waiting beyond it. A painting as much about growing up as it is about the pleasures of childhood, the work tempts us to see here a portrait of the artist himself as a young boy and the breadth of time from present to past. From time to time in Wiltraut’s paintings, we get the feeling that we’re looking at a lost world, or perhaps at a world that is being lost, and in the process discover it all over again. In Looking at the Moon, a painting about “lost and found,” an outdoorsman delights in reclaiming a precious relic of childhood, a simple but striking marble. This portrait of Wiltraut’s friend Bob also celebrates the artist’s own collecting instincts and the value he places on everyday treasures. “Nature was a major passion with my family,” he says. “Camping trips exposed us to every facet the woods and streams had to offer.” Describing his boyhood, Wiltraut recounts collecting everything from fossils in the Dakota Badlands to bottle caps—his first experience with color—to agates on the shores of Lake Superior and butterflies in the Carolinas, and the moment of discovery always gave him a special thrill. “There was never a shortage of exposure to the magnificence of Nature,” he says. “It opened my eyes, and I drank it in.” Meredith E. Lewis is a freelance writer and editor based in Manhattan. Download this article in its original printed form

|

||||||||

|

©Copyright 2004 Douglas Wiltraut. All rights reserved. |

||||||||